Hey friends, welcome back to Think Bitcoin™ for issue #23. As always, if you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out!

In this issue:

Headlines/Insights: Why the personal finance community doesn’t get Bitcoin

Content Round-Up: 1 paper, 1 video

As always, if you find this newsletter interesting or useful, please share it with others who might find it interesting or useful, too!

Headlines and Insights

Why the Personal Finance Community Doesn’t Get Bitcoin

Personal finance has grown into a veritable juggernaut of an industry. Its ecosystem teems with influencers and products. It has even made it onto CNBC in the form of their “Make It” page. For the sake of simplicity, I am using “personal finance community” rather broadly to include within its purview the FI/RE (Financial Independence/Retire Early) community, as well, and will refer to it all as the “PF” community/space for the rest of this piece. I also want to acknowledge from the outset that I do know not everyone in the PF community is the same or feels the same way. However, in my experience writing and creating content in the space, it is certainly true that its core tenets are rarely questioned.

The overarching purpose of the PF space is to increase financial literacy, promote good financial habits, and help folks prepare for and, ideally, accelerate retirement, by championing buying and holding index funds. Surprising as this may sound to some (though not to those who have done their homework), Bitcoin promotes many of these same ideas. Properly understanding Bitcoin requires one to learn about macroeconomics, economic theory, and monetary policy, among many other things, which is to say it promotes not merely financial literacy, which too often is simply code for knowing how to budget, but also economic literacy. Understanding Bitcoin also has a profound effect on one’s economic behavior. It lowers one’s time preference, encouraging delayed gratification and living below one’s means, something the PF space would certainly agree this is an unimpeachably good financial habit. Finally, Bitcoin is the best-performing asset of the last 12 years which, for people who love to take past results as proof of future results (looking at you, PF people) should at least warrant a good-faith examination as an asset that could aid in successful retirement planning.

Despite the foregoing, the PF space (with few exceptions) is not a fan of Bitcoin (let alone the wider world of crypto). So why doesn’t the space embrace Bitcoin? Perhaps more importantly, why is the space so devoid of quality Bitcoin content?

As someone whose work regularly intersects with the world of personal finance creators, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about these questions. I think there are several reasons that explain the PF community’s current posture toward Bitcoin, most salient among them:

Blindness to risks in the orthodox PF investing strategy

A failure to understand and account for the changing macroeconomic environment

Disproportionate focus on past results

General aversion to risk

A collective information diet that is an echo chamber

Let us examine each one, in turn.

1. Blindness to risks in the orthodox PF investing strategy

The PF community fails to appreciate the risks of its party-line strategy of simply buying and holding broad-market index funds in a price-insensitive manner. A very common refrain in the personal finance space is that the only way a total market index fund can dramatically fail is if every company in the S&P 500 collapses. Some examples (and I assure you these are only a few of the seemingly infinite amount):

(Note: I cite these examples not as any personal commentary on these accounts, but as an illustration of how common and prevalent this kind of content is. No disrespect to the creators).

The point is that if you believe these things, why would you ever bother investing in anything else? If you truly believe the only way your investment could fail is if World War III ensues; and that, absent global war or the plague or a total collapse of society, your investment is guaranteed to pump out 10% or 15% in gains every year, why would you consider investing in anything else?

Like many of the fundamental tenets of the PF space, the aforementioned beliefs are a bit reductive and not very nuanced. For starters, this isn’t how index funds work. I find it endlessly troubling when I see the very folks who sell courses on index fund investing demonstrate, over and over, their own misunderstanding of the very thing about which they claim (and sell) expertise.

There’s a difference between pondering whether the S&P itself will go to zero (which doesn’t make any sense) and pondering whether an index fund that tracks the S&P could go to zero. Most PF creators seem to mean the latter, which, alluring as its certainty may be, is not wholly correct.

The explanation for why an S&P index fund can, theoretically, go all the way to zero without every company being wiped off the planet or having zero profits is most eloquently and rigorously articulated by Mike Green, Portfolio Manager and Chief Strategist at Simplify Asset Management.

Here’s the condensed explanation for why this tenet of PF investing is not technically correct. What most refer to as “passive” investing is, definitionally, not passive. It’s price-insensitive active investing, meaning it still very much involves buying or selling. These actions are just done in a price-insensitive manner. When you buy an S&P index fund, the fund receives your money and automatically makes a buy. Each incremental dollar received is used to buy, in proportion to the market cap weight (if a market-cap-weighted fund) of each company in the fund.

What most folks don’t understand is that this is all completely price-insensitive. The only signal that the index fund responds to is inflows and outflows. When money is received (inflows), the signal is to automatically buy. When money is withdrawn, the signal is to automatically sell. There is no one performing any valuations or assessing the fundamental value of the companies or reflecting on the financial position of these companies, etc. There is no research and no diligence. The only thing that matters is whether money is coming in or going out.

The whole idea of “passive” investing is essentially to ride the coattails of active investors, whose research and diligence would facilitate price discovery and proper price signals. But when this kind of passive investing becomes a larger and larger percentage of the market, it affects the market. The higher the percentage of passive, the higher the percentage of investors acting price-insensitively, the more warped the market becomes, the more obfuscated price discovery becomes, which leads to all kinds of downstream issues. This is why Jack Bogle himself, the inventor of the index fund, said in 2017:

“If everybody indexed, the only word you could use is chaos, catastrophe. There would be no trading. There would be no way to turn a stream of income into a pile of capital or a pile of capital into a stream of income.”

He understood this. The PF space often assumes the market is perfectly efficient without taking into account how their collective price-insensitive behavior distorts this very idea.

Because inflows and outflows are the sole signal to which a passive index fund responds, a passive index fund can, in theory, go to zero if there’s a massive outflow event, without anything actually changing about the companies that comprise the index. Similarly, it can remain high, despite multiple catastrophes, if inflows keep steadily coming into the fund. The performance of the fund has little to do with the health of the companies (remember, no one is evaluating this). It is simply about inflows and outflows.

Now, I want to be clear. I don’t think it’s likely that index funds would go to zero. In fact, I think it is extraordinarily unlikely. But that doesn’t mean the growing market share of price-insensitive “passive investing” isn’t warping the contours of the market, nor does it mean that S&P index funds can’t drop precipitously on a major outflow event, which may have nothing to do with the companies that comprise the index. For example, millennials are the major investors in passive index funds. If when millennials start retiring, they begin unloading these funds in increasingly large amounts (as demographics dictate), and the inflows from the next generation are simply not there to scoop up these outflows, then the price will drop until buyers are found. If the outflows are enormous and the inflows comparatively small, the price drop would be significant. And it would have nothing to do with the companies in the S&P 500 having zero profits or going bankrupt. This risk increases the greater the market share of passive investing.

Another oft-overlooked risk of the traditional PF strategy is how the historic expansion of the money supply over the last 14 years (particularly over the last two years), has affected what we perceive as gains. So let’s talk about these 10%-15% gains that everyone expects to magically accrue every year. And let’s begin by never forgetting this:

Wealth is purchasing power. It is not a dollar number, nor is it a number on your computer screen.

Obsessively focused on increasing the dollar number in an investment account on a computer screen, the PF space almost uniformly fails to appreciate this distinction. To be fair, it is a subtle distinction, and many others struggle with it, as well.

It becomes increasingly important to understand, however, when the tools at the disposal of the Fed and the Treasury Department, respectively, are increasingly utilized in ways that juice the dollar number without commensurately increasing the corresponding purchasing power of that dollar number.

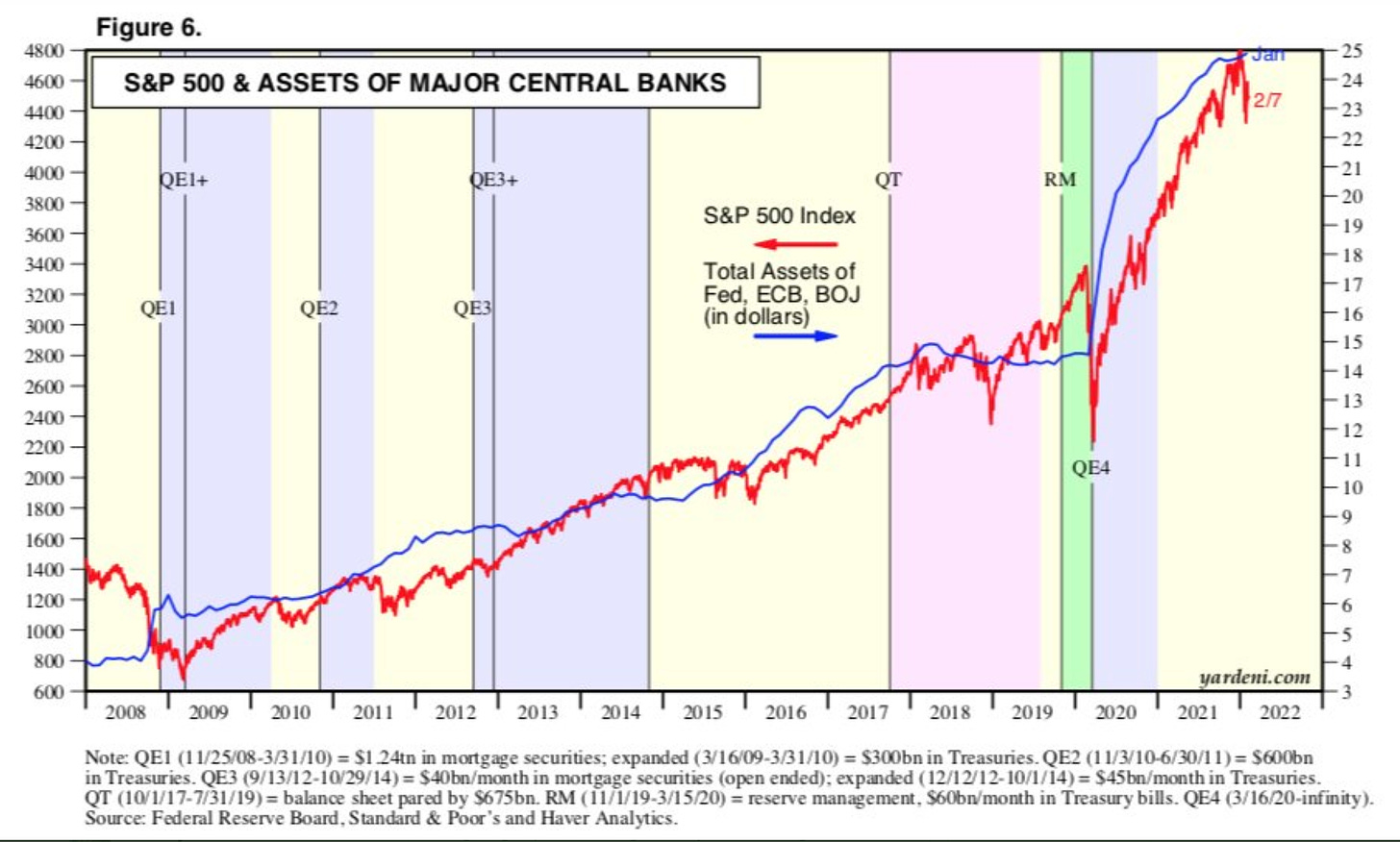

When we simultaneously expand the money supply at an unprecedented rate and keep interest rates artificially low, we create an environment that propels asset-price inflation. Because of the Cantillon Effect, the new flood of liquidity goes first to financial institutions, corporations, and the wealthy who, collectively, own the overwhelming majority of the assets in this country. And they kept buying them. The glut of liquidity, therefore, ultimately ends up in assets, which inflates their respective prices. This is why the stock market has been moving in lock step with central bank balance sheets over the past decade or so, the expansion of which is the result of quantitative easing.

What all this means is that stock market gains are misleading. Since 2008, they’ve accrued in rough proportion to the size of central bank balance sheets. Sure, the dollar numbers are getting larger, but the purchasing power represented by those numbers is not increasing nearly as much. Purchasing power, which is real wealth, is being degraded by the money supply expansion.

Everybody proclaiming that the stock market emphatically “recovered” from March of 2020 should ask whether it recovered or whether it was just caught, back-stopped, and then propped back up again by massive liquidity injections and artificially low interest rates. Put differently, are you really getting filthy rich or is the unit you’re using to denominate your wealth just being debased? If you’re focused on the number on your computer screen, you probably think you’re getting filthy rich and that the stock market is a magical, implacable machine. If you’re focused on purchasing power, however, the story is far less sanguine.

Another common (and related) refrain in the PF community is “invest x amount of dollars a month and you’ll be a millionaire in 30 years.” Again, if you are focused solely on the dollar number, this sounds great. But the purchasing power of a million dollars in 30 years is radically less than the purchasing power of a million dollars now.

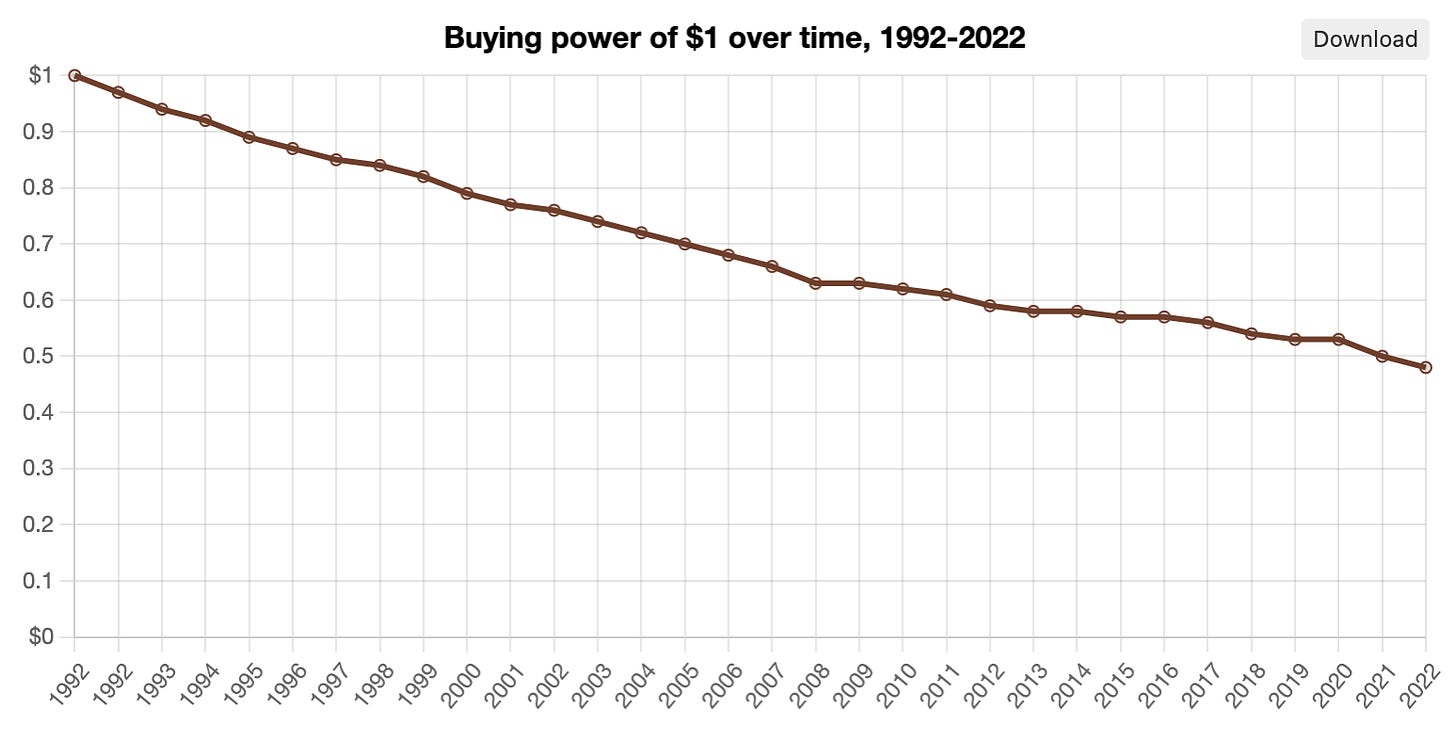

One dollar in 1992 is worth two dollars today. This means if, in 1992, you set a goal to have $1 million worth of purchasing power in 30 years, you would need $2 million in 30 years to achieve that. Again, this is the difference between wanting a million dollars and wanting a million dollars in today’s purchasing power 30 years from now. For the former, sure, you merely need to cross that dollar figure number. For the latter, you are, at best, going to need double that dollar amount.

Keep in mind that in this 30-year period above, inflation was only over 3% in seven of them (8 if you count the still in-progress 2022). It was only over 4% once (2021). The average CPI inflation rate was 2.34%. This was a historically low period of inflation and you still lost half your purchasing power over that time. Imagine if it was a worse period for inflation.

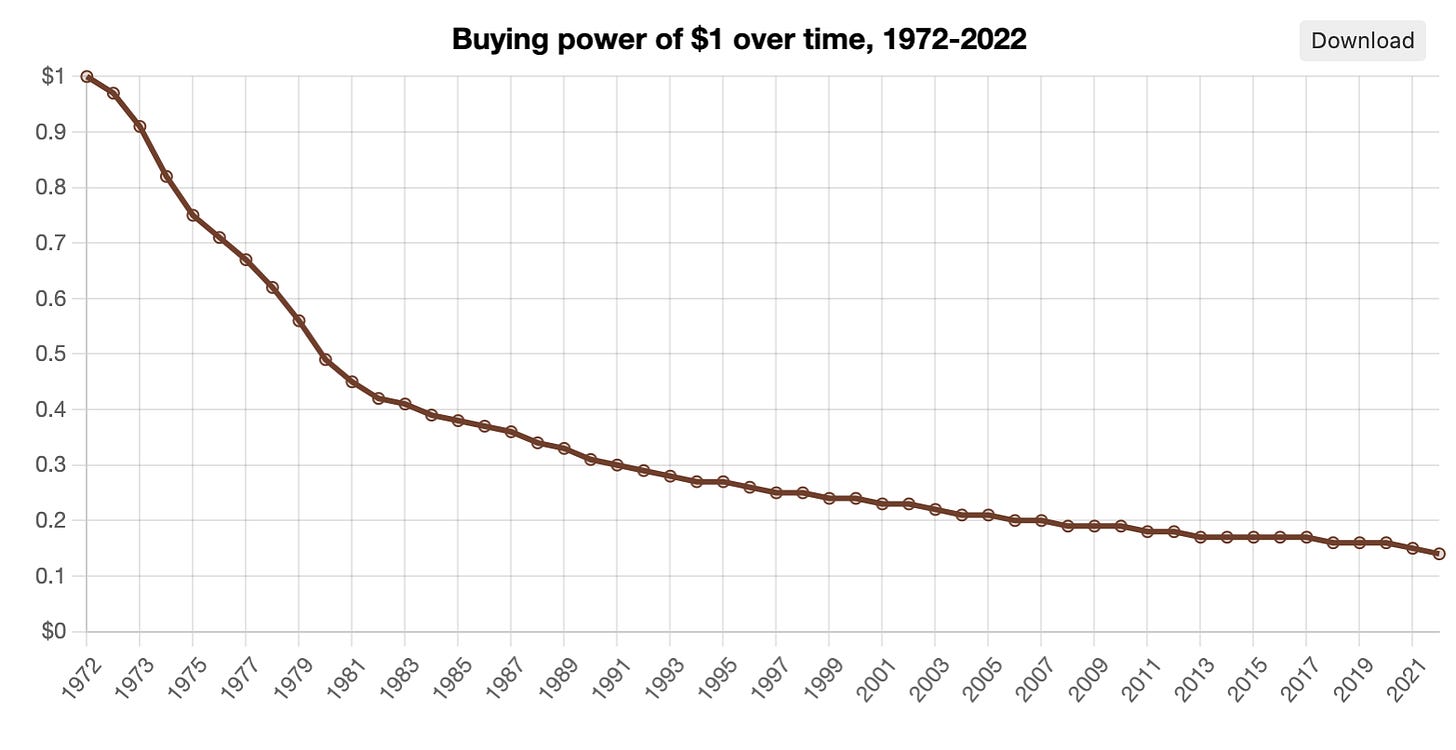

One dollar in 1972, for example, was worth $4.30 in 2002. The average CPI inflation rate over this 30-year period was 4.99%. This means if you had a goal, in 1972, of having $1 million worth of purchasing power 30 years later in 2002, you would need between $4 and $5 million.

This is what goes unacknowledged and unsaid in the PF space. When we all talk about wanting to have $1 million in 30 years, what we really mean (or what we envision in our minds) is $1 million in today’s purchasing power. We do not wish merely to have $1 million in 30 years if it only represents $250,000 or $500,000 in today’s purchasing power. But that’s how it works.

2. A failure to understand and account for the changing macroeconomic environment

The PF investing strategy essentially rests on a series of macroeconomic assumptions, the existence and importance of which most proponents are not aware. These assumptions can be bluntly distilled into an overarching belief that the geopolitical and monetary conditions that have allowed for the last 40 years of unprecedented U.S. stock market growth will persist unchallenged and unchanged for the next 40 years, thereby facilitating an equally unprecedented future of stock market growth.

The last 40 to 50 years saw the birth and growth of the petrodollar system and the fall of the USSR, which made the U.S. the undisputed global hegemon. The petrodollar system is worth a brief explanation, since I have not once seen or heard a PF influencer on any platform discuss the financial and political implications of this system, let alone demonstrate any understanding of its existence.

The petrodollar system, for those who don’t know, emerged when Nixon took us off the gold standard in 1971. Unable to keep the currency pegged to gold, the administration looked for ways to preserve the global supremacy of the U.S. dollar. The result was a series of agreements with Saudi Arabia (and, later, other oil-producing countries in the Middle East, too) in which they agreed to price all oil contracts in USD, in exchange for which the U.S. promised to provide defense.1

This was beneficial to the U.S. because we were (and are) running up a ton of debt. Saudi Arabia agreed to take the profits from their oil commerce, commerce which was conducted in dollars, and buy United States debt. To radically summarize how this shaped the global economy, every country needs oil for energy, so most countries needed dollars to pay for the oil. This created a global demand for dollars, which strengthened the U.S. dollar, which, in turn, made our exports uncompetitive. This contributed to the destruction of our manufacturing industry and weakened the middle class. This accelerated the financialization of everything, as financial services became one of our leading industries.

Sustaining the petrodollar system has required the U.S. to intervene militarily at various times and in various ways, much to the obvious detriment of those called upon to fight, the taxpayers, and the environment. After all, the U.S. military is itself the world’s largest institutional consumer of oil and, since 1971, has been deployed in several instances, whether indirectly or directly (debates rage), to defend a system entirely predicated and dependent upon the production of oil.

However, this system, which has governed and coordinated the global economy for about 50 years is beginning to fray. Unsurprisingly, not every country is thrilled about financing U.S. debt and the privilege that global reserve currency status has bestowed upon the U.S. We are now seeing efforts from countries like China and Russia to de-dollarize.2 Both countries are also stockpiling gold. The Fed is now the largest purchaser of United States debt, as countries like China have decided they no longer want it.

What does this all mean? It clearly means we’re moving toward a world that is multi-polar, with regional powers dominating different spheres of influence. It means we seem to be progressing toward a geopolitical state of affairs in which the U.S. is not the singular hegemon. And it may also mean we eventually see a world in which U.S. debt and U.S. dollars are no longer the global reserve asset and currency of the world. This has profound geopolitical and economic implications that absolutely must be considered if you are looking to manage investment risk into an uncertain future.

Lastly, our national debt has crossed the 130% debt to GDP ratio, which, historically, is an extremely important harbinger of what’s to come. Brian Hirschmann of Hirschmann Capital did a study of all the countries that have crossed this debt to GDP threshold. Of the 52 countries, 51 defaulted in some way, whether via an outright default, a restructuring, a devaluation of the currency, or hyperinflation. The only country that did not default was Japan, but they, unlike us, were not a twin-deficit country.

The default does not always happen right away. For example, Spain crossed the threshold in 1869 and didn’t ultimately restructure their debt until 1877. The United Kingdom crossed it in 1919 and devalued their currency in 1931. It took Ghana six years from reaching 130% debt to GDP in 1960 to restructure. Germany hyperinflated in 1922 after crossing the threshold in 1918. In 2010, Greece passed the threshold as a result of the 2008 financial crisis. They were bailed out that same year.

There is little reason to expect that our national debt will be meaningfully reduced or addressed in the future. There is simply no political will to enact the type of measures necessary to do it, measures that would have severe effects on the global economy, which itself is entirely debt-driven.

As Ray Dalio has noted, there are only a handful of ways out of debt this big. The options are essentially austerity, default, or inflating the debt away. None of these options is great for the stock market. Austerity and outright default would be devastating. Inflating the debt away via expansion of the money supply feels good initially, as much of that liquidity pools in assets, increasing their dollar value. But this process obviously debases the value of the dollar.

Sure, the Fed will take some near-term steps to address inflation, but they are ultimately facing a terrible choice: act aggressively on inflation and risk crashing the markets (and also increase the cost to service the national debt) or keep printing, which would erode the value of the debt and keep the stock market high but risks significant social unrest. We could get some near-term deflation as the Fed attempts to rein in inflation, but how much deflation can an economy built on debt sustain before something breaks and the Fed has to step in again?

Suffice to say, we have never been in this position before. We are a twin deficit country with a debt to GDP ratio over 130% and no way to bring it down without causing significant pain.

Complicating things further is the world’s increasing dependence on Russia and China for natural resources and manufacturing. China is the world’s biggest manufacturer (and it’s not close), and Russia is the biggest supplier of natural gas to Europe. Russia and China recently struck a 30-year deal for the former to supply the latter with gas through a new pipeline. Russia, as I write, appears on the verge of invading the Ukraine. Our typical method of deterrence and punishment is sanctions, but in a world where Russia is less dependent on dollars (due to a cozier relationship with China, who, again, is also de-dollarizing), the sanctions are less crippling.

So, to recap, the macroeconomic conditions that have existed for the past 50 years and which have enabled and facilitated the unprecedented rise of the stock market over that time are changing. We’re in a position of indebtedness we’ve never been in before; we’re no longer the world’s sole, undisputed hegemon; and the system that has ensured the dollar’s supremacy as the definitive global reserve currency (and U.S. debt as the global reserve asset) is unmistakably breaking down.

This means the next 50 years are not going to be the same as the last 50 years. But if you didn’t appreciate the macroeconomic conditions underpinning the market for the last half century, you would fail to notice or appreciate the consequences of these conditions changing.

3. A disproportionate amount of focus on past results

The sole data point that the PF community uses to inform its investment strategy is past results. In other words, whereas regulated institutions are not legally allowed to guarantee future returns based on past results, this is a guarantee that PF creators make repeatedly, almost robotically, with no reservations or qualms.

But when they talk about past returns, what they’re really talking about is returns over the last 40 years or so. Christopher Cole of Artemis Capital, writing in January of 2020 (i.e. before COVID and the massive subsequent money supply expansion), noted that 91% of the price appreciation for a classic 60/40 portfolio over the past 90 years came from a 22-year period between 1984 and 2007. He further found that 94% of returns from domestic equities come from the same period. Imagine what those numbers are now, given that the S&P, buoyed by the liquidity deluge of the last two years, has since roughly doubled?

The lesson here, and the primary takeaway of Cole’s paper, is that the last 40 years have been extraordinary in terms of their returns. But, historically, they are far from the norm.

Nevertheless, PF orthodoxy not only assumes the next 40 years will mirror the previous 40; it depends on it. Now, if you believe that the macroeconomic conditions of the last 40 years will persist over the next 40 then, by all means, carry on. However, if you’re only data point for making this determination is a chart of the S&P from 1980-present, then your investment strategy is not a strategy. It’s merely a hope that nothing changes.

Moreover, this fixation with the past cuts both ways. It renders one less likely to perceive both risk and opportunity in the future, which is to say you’re more likely to miss both the shifting paradigm and the window in which to take advantage of the shifting paradigm.

As an aside, the fixation with past results, coupled with a blindness to the macroeconomic factors that enabled these results, creates interesting and, at times, confused political positions. Many PF influencers anchor their wealth entirely to the health of the U.S. stock market and, simultaneously, advocate for policies that would further debase the value of their stock market gains and/or usher in an economic environment less conducive to the achievement of those gains in the first place.

It’s common in the PF space to treat index fund investing as a kind of resistance to the establishment. Many boldly state that that the government “doesn’t want you to be financially literate” and invest in index funds, as if it’s some kind of revolutionary secret. The idea that it’s revolutionary for every American’s net worth be 100% tied to the health of the stock market, which is driven by debt and increasingly dependent on the intervention of an unelected group of people at the Fed, seems obviously self-contradictory, but that doesn’t seem to dilute the narrative. For reasons I’ve written about constantly in this newsletter and elsewhere, Bitcoin - not index funds - is the truly revolutionary asset, the societally transformative monetary technology.

4. General aversion to risk

Why the fixation with the past, though? At its core, I think the PF community is deeply risk-averse. Many creators and adherents are folks who have paid off (or are paying off) significant debt, and the ubiquitous prescriptive advice in the space is essentially to reduce risk as much as possible. As someone who has paid off six figures of student debt, I very much get it, and I don’t fault people for this perspective. Having to pay off large amounts of debt profoundly influences financial behavior and perceptions of risk.

There is a genuine, palpable belief in the community that there is very little risk in the stock market. Index funds are essentially treated as risk-free savings accounts over the long-term, despite the steady degradation of the denominating currency and the effect of passive investing on market dynamics, which I discussed above.

The grounds for this perception of the stock market are, of course, its past returns. I’ve had multiple discussions with PF influencers who have expressed a willingness to think about Bitcoin only if it establishes a history as long as that of the stock market. Being the best-performing asset over the last twelve years and growing in adoption faster than the internet is not enough. The increasing interest and investment from financial institutions, including banks, insurance companies, and investment firms, is not enough. The PF space needs decades of historical returns before it gets comfortable.

I would argue that this is a collectively reinforced behavioral norm masquerading as an investment strategy. Assessing the probability of a given future outcome and investing accordingly is a strategy. Betting that the future will be exactly like the past as a matter of course is just Pavlovian.

5. A collective information diet that is an echo chamber

Many PF influencers began as PF content consumers. They are swiftly led to believe, through the sheer weight of homogeneous advice, that, like the truth and beauty of Keats, all one needs to know is that an S&P index fund can’t fail, the stock market always goes up, and these things never change. These folks, once mere consumers of PF content, emerge from this chrysalis of education as influencers and content creators, themselves. Newly baptized, the next step is usually to create a course and attempt to profitably share this investment advice with others.

The result, though, is that many in the PF community consume an information diet disproportionately comprised of their peers in the space and not, for example, from professional investors, investment analysts, macroeconomic researchers, Bitcoin experts, crypto specialists, etc. A typical PF creator is not reading Pantera Capital’s Investor Letters to get a handle on the crypto landscape, nor is he or she learning about Bitcoin through the work of Lamar Wilson, Saifedean Ammous, Lyn Alden, Nic Carter, or Alex Gladstein. He or she is likely absorbing Bitcoin information through mainstream financial headlines and the occasional Bitcoin post from a fellow PF influencer, which he or she may then repackage and regurgitate as original content.

One of the reasons I started this newsletter was to address precisely this problem. I wanted to expose interested folks in the PF space to the writers, thinkers, and operators in the Bitcoin space, in an effort to upgrade the quality of Bitcoin information they receive. I very much believe we need better bridges from the PF community to the Bitcoin community, and I personally intend to continue to try to build them.

To radically summarize, the PF community doesn’t understand the underlying conditions that have enabled the stock market to perform the way it has performed over the last 40-50 years and so is ill-equipped to notice when those underlying conditions change. It’s like not knowing (or misunderstanding) why it rains, but nevertheless guaranteeing it will rain tomorrow because it has rained the last seven days.

For the PF space, the metaphor of the orange pill is painfully apt. Many of its adherents and acolytes live in the Matrix, unable to see or notice the manipulated reality constructed around them. Like Neo, who was given a choice to see the truth or remain blissfully unaware, they have a choice. And it is our job as Bitcoin writers and thinkers to help them internalize the gravity of this choice. Because real life isn’t a film. The consequences aren’t fictional.

Content Round-Up

1. “Bitcoin First: Why Investors Need to Consider Bitcoin Separately From Other Digital Assets,” a paper written by Chris Kuiper and Jack Neureuter, Director of Research and Research Analyst, respectively, at Fidelity. This paper is both a good primer for those relatively new to Bitcoin and also a good framework for thinking about the differences between Bitcoin and other digital assets.

2. “The Environmental Impact of Bitcoin,” a video by the good folks at Hello Bitcoin, featuring Audrey Strobel. As I’ve talked about on countless occasions, there’s an ever-increasing amount of criticism circulating about Bitcoin’s energy use that relies on or promotes false premises with respect to how and for what purpose Bitcoin uses energy. This 8-minute video does a great job of explaining how and why Bitcoin uses energy, why it’s actually a positive development for the environment, and how it contributes to the fight against climate change.

Bonus/Miscellaneous

Michael Saylor, CEO of Microstrategy, hosted his second annual Bitcoin For Corporations conference two weeks ago. It featured this gem of an interview with Jack Dorsey:

As always, thanks for reading! If you enjoyed it or found it useful, share this newsletter widely and freely!

“Civilization is in a race between education and catastrophe. Let us learn the truth and spread it as far and wide as our circumstances allow. For the truth is the greatest weapon we have.” -H.G. Wells

See you next week,

Logan

SUPPORT

Send bitcoin to my Strike

SOCIAL

DISCLAIMER: I am not investment advisor and this is not investment advice. This is not, nor is it intended to be, a recommendation to buy or sell any security or digital asset. Nothing in this newsletter should be interpreted as a solicitation, a recommendation, or advice to buy or sell any security or digital asset. Nothing in this newsletter should be considered legal advice of any kind. This newsletter exists for educational and informational purposes only. Do your own research before making any investment decisions.

© Copyright The Why of FI.

For a deep dive on the petrodollar system I recommend reading “Uncovering the Hidden Costs of the Petrodollar,” an article by Alex Gladstein and watching Petrodollars, a film by Richard James.

E.g., https://www.usnews.com/news/top-news/articles/2022-02-04/exclusive-russia-and-china-agree-30-year-gas-deal-using-new-pipeline-source

Very good read! 👍🏼👍🏼